"Erasure as a sign of protest”: Graffiti from 2019 pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong

Interview with Hans Leo Maes by Jordan Hillman and Sabrina Dubbeld, conducted for the international colloquium “Pratiques urbaines : expériences sensibles” held at the German Center for Art History—DFK Paris, on June 27 and 28, 2022.

Sabrina Dubbeld: Hans, you are an architect but you are also a photographer. As part of this activity, you covered the “pro-democracy” protests that took place in Hong Kong in 2019. Your photographic work led to the publication of the book, Nothing to see here (fig. 1), in 2021, in which, in addition to the photographs, you wrote a very personal text about your practice, but above all about these graffiti, their erasure, their traces. Before talking about this book in detail, the circumstances of its realization and publication, can you tell us about your background: how you got started as a photographer, and more specifically as an urban photographer?

H. L. Maes: Actually, I am an architect. I am from Belgium but over the last twenty years, I lived around 15 years in Asia: first in Singapore, then Hong Kong and then in Bangkok for a short time. Then I went back to Belgium more than ten years ago. I wasn’t working too much as an architect, so I started photographing and showing my photos on Instagram. I don’t pretend to be such a professional, but I was doing that a lot, mainly in Antwerp and its harbor. And when I returned to Hong Kong in around 2013, I started to be a bit more professional and got a proper camera. As an architect, I really like walking through the city kind of unplanned, in a “dérive” kind of way, documenting the kind of urban constellations that you don’t maybe associate with Hong Kong. It’s a very photogenic city but people seem to be always photographing the same things. So, I was really interested in going to places where expats and tourists would seldom go like the housing estates, the more industrial areas, and the like. I think it does have a little bit of a relation to my later interest in the graffiti because I always like to look at the backside of things or structures that are not the focus of the action. I am very intrigued by these kinds of spaces and buildings; I will do a next book about “undercrofts,” the exposed foundation structures necessary for constructing apartment buildings on hillsides. For me this is very spectacular. As an architect I am interested in the unplanned urban constellations which are a result of Hong Kong’s density where everything is built very closely together so you get very interesting juxtapositions.

The countless construction sites in Hong Kong I find very intriguing as an architect also: what buildings look like before they get beautified—if they ever get beautified. “The Guardian” made an article about the photos I did of stairs because there are a lot of public stairs in Hong Kong as a result of its topography.

Yeah, this is kind of my background. About two years ago I lost my architect job because of the impact of the political unrest and because of Covid. Since then, I am freelancing as a designer and as a photographer and started writing more also.

Jordan Hillman: It seems like your photographic and architectural practices are significantly intertwined. Do you produce work under the same pseudonym for both? Is this for a practical or a creative purpose for you?

H. L. Maes: So yeah, my pseudonym is “TypicalPlan”, not for reasons of anonymity per se, rather as an architect I am uncomfortable with this personality cult of starchitects, so I chose a very generic company name as a kind of joke, which is “TypicalPlan.” This refers to a term in architecture: when you have an apartment building you have a ground floor plan with the entrance and above you get the floors with apartments with a “typical plan” that is generally the same on every floor, so it’s like the generic thing. The name points to a kind of generic nature of my practice in that I do basically anything I am interested in and do not just do design or architecture.

Sabrina Dubbeld: Let’s go back to 2019. What led you to want to cover the protests then taking place in Hong Kong? Did you have the opportunity to follow them from the beginning? Did you attend all the protests?

H. L. Maes: So, there was a protest in 2014, which a lot of people may remember but maybe less so in Europe. Just after I came back to Hong Kong there was the “Umbrella Movement”. This was really the moment of resurgence for the “Pro-Democracy Movement” in Hong Kong and marked a generational change because this was very much driven by students and young people. I don’t have any photos of these protests in 2014. It was a time where a lot of students built a camp in the commercial center of Hong Kong and blocked all traffic and they literally “took back” the streets. They built a kind of alternative society in the commercial heart of Hong Kong. This was very interesting to me, maybe more interesting than the movement in 2019, which was way more confrontational. They built an extremely well-organised village where people had desks to study, recycling stations and first-aid stations, and it was very fascinating to see. I think people will realize one day how significant it was.

This movement was spurred on by the way that China interpreted the concept of universal suffrage, stipulating that candidates for chief executive had to be vetted first by Beijing.

So, then 2019 was very different. This was because of the extradition bill where people arrested in Hong Kong could be extradited to China. Because previously people had been kidnapped from Hong Kong to be brought to court in China, this made people concerned, and it was seen as a potential threat to freedom of expression. Although the extradition bill was withdrawn after a few months, by then the protesters had formulated five demands—like real universal suffrage—and this did not put a stop to the protests.

Jordan Hillman: Did you attend any of the protests? What was your role in or relationship to the protests as a person who had only lived in Hong Kong for 6 years at the time?

H. L. Maes: As a so-called expat, I was always in between a local and an immigrant, being a by-stander/observer and a participant at the same time. I was interested in what was happening, so I did go to a lot of protests, but I always felt a little on the margins. You barely ever saw a foreigner or white person protesting—although you have to take into account that Hong Kong is ethnically very much Chinese. So, I don’t even know what my role was exactly, but I was kind of observing and sometimes taking photos.

I went to the big 2 Million March protest. There were other events like the human chain across Hong Kong. The protests were characterized by a lot of creativity, citizens came up with new ways of resistance because after a while regular protests were increasingly banned.

It’s the same as most places I guess, where you must get an official approval for a protest. But in Hong Kong, after a while, all forms of protests were declared pretty much illegal.

I remember once at night when the government had just imposed the anti-mask-law, the police had withdrawn so people were going out to protest and some were smashing in shop windows of China-affiliated businesses and taking some bulldozers from construction sites and were driving them around. So, at times there was really a feeling of “this could go anywhere,” of things spinning out of control.

Jordan Hillman: There was a huge surge in graffiti production during the protest in 2019, but was there a Street Art scene before that in Hong Kong?

H. L. Maes: I am not at a graffiti art expert. I was drawn into this kind of aesthetics and before I wasn’t really too interested. But I find that definitely in the last few years, a lot of street art was commercialized and became just a background for taking your Instagram photos.

Jordan Hillman: Was photographing the demonstrations dangerous in other ways? How did you adapt your artistic practice and your physical practice to what was going on with the Chinese authorities and their policies?

H. L. Maes: I didn’t really seek out to be anywhere near where there was police intervention, so I stayed away. But the artistic practice is another thing, because I published this book, and I was also writing a text.

A little thing happened in Hong Kong which was the national security law, which is a very broad-ranging and deliberately vague law. It does not just apply to Hong Kong citizens or those in Hong Kong but covers people all over the world.

So me, as an expat, I can probably do and say a little bit more. But people in Hong Kong like artists and journalists are constantly negotiating and making estimates of “What can we say”, “What can we do?”. This is a continuous kind of thing but as for myself, I always try to be measured in my work, without limiting my expression. Sometimes this kind of pressure also helps to make your work more subtle.

Sabrina Dubbeld: Since you talk about “what you can say” and “what you can do,” I would like to take this opportunity to ask you about the different forms of censorship that have affected the graffiti produced by the demonstrators in 2019. How, in turn, the protesters have at the same time ‘adapted’ to the situation by subverting it. In your book for example, you often capture the use of the paint-over method, but it seems that the authorities also used fabric to mask it ...

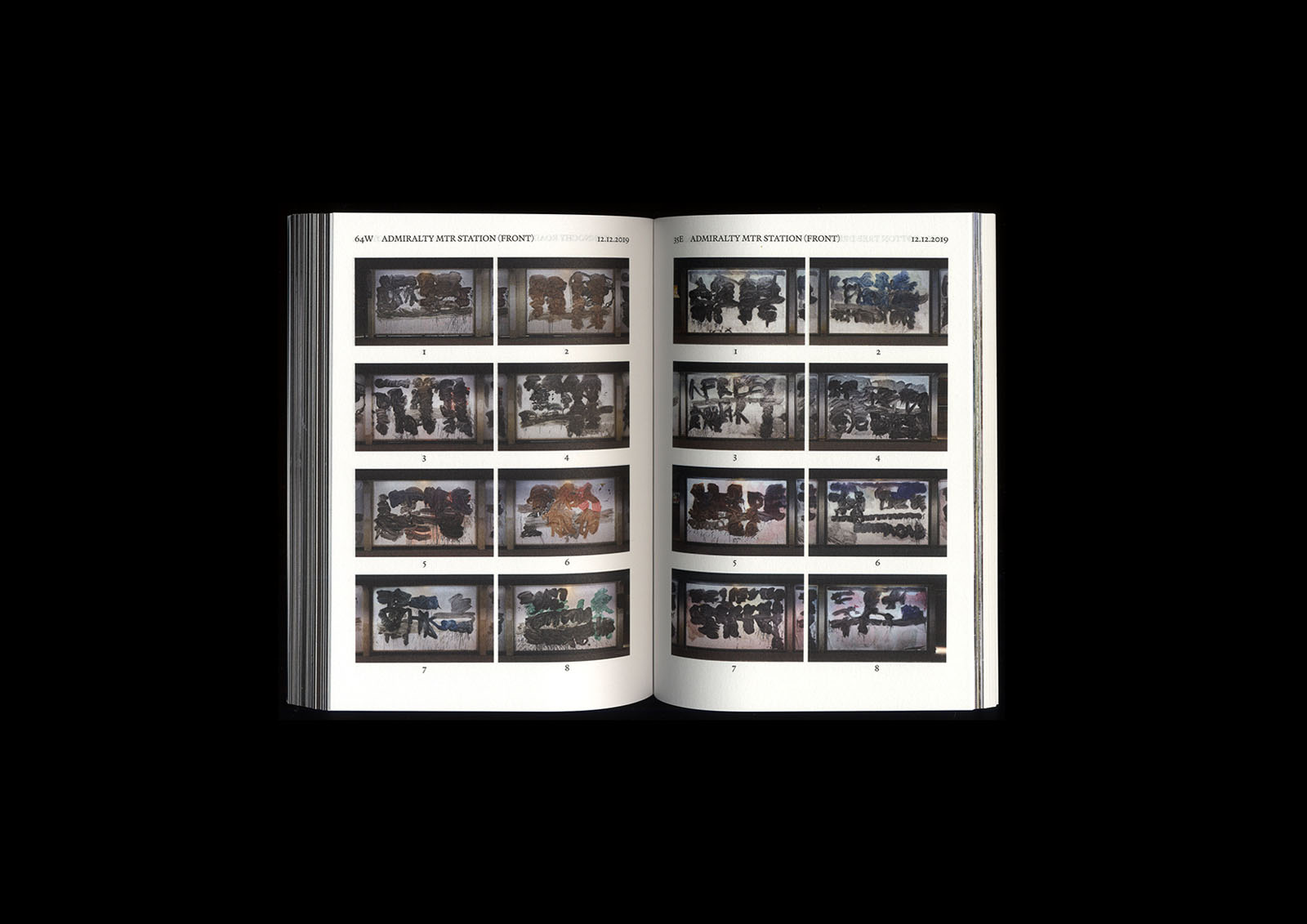

H. L. Maes: I was really intrigued by the aesthetics of the erased graffiti. I was just trying to document these things and started putting the strategies of graffiti erasure in categories. This is all to be found on my website—in the book (fig. 1, 2) I focus more on the tram stops where the graffiti were smudged out. You also had the simple geometric paint cover-ups which looked like a Malevich painting (fig. 3). Sometimes someone comes along and writes something on it, because, ironically, every time a cleaner comes and covers it up, this is a new blank canvas.

Here you see how (fig. 4) it was covered up in a really geometric way. During the protests this is everywhere in Hong Kong, on nearly every floor, every ceiling and every wall of public space. As an architect, this three-dimensional spatiality interests me. Here are photos (fig. 5, 6) of the same cover-up strategy in different situations. Someone covers it up, someone writes another slogan, someone covers it up and so on. If they want to get rid of it very fast, they tape plastic sheeting over it and you get this strange kind of ugly aesthetic (fig. 7, 8).

The funniest thing is when they cover it up so closely that the original message is still readable, just in a different color or written in bold. These Chinese letters are still pretty readable (fig. 9, 10). In my book, I also show cases where they tried to wipe graffiti out, but they had limited success. This is interesting: can anybody read this? If I ask this in Hong Kong everybody will immediately recognize this. This is still readable when you know the common slogans of the protest movement; it’s like a kind of a code which is still readable for those in the know.

Sabrina Dubbeld: One interesting thing is that censorship makes the phenomena of invisibility and visibility all the more acute and draws attention to the fact that there is always something going on...

H. L. Maes: This goes back to the statement in the title of the book. And this refers to my specific position as a non-Chinese speaking expat, but a lot of Hong Kong citizens were also fascinated by these remains of erasure. I think it has to do with the fact that the slogans were very specific and literal. Within the protest movement there is a whole range of people against the Chinese communist party ranging from Trumpists to very left-wing grassroots movements. So, the specificity of these different slogans, kind of exposed those different factions within the movement. But when the specific messages were erased, the erasure became a universal sign, it became a sign of repression, of a crackdown on freedom of expression.

And so funnily enough, I believe this repression helped to galvanize the social movement. The graffiti is a good expression of this, but it applied more generally. The pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong has always been weak because of different factions, but because of this blanket condemnation and repression by the government, it helped galvanize people from different political persuasions to come together. The graffiti erasure was really a powerful metaphor for this I think.

Sabrina Dubbeld: Your book, Nothing to see here, was published by Building Books, a French publisher based in Paris. Could you tell us a bit more about your choice to publish a text and your photographs on the Chinese protest movements in France? Also, at what point did you have the desire or the idea to publish this book? And what were your editorial choices?

H. L. Maes: Only yesterday I met them for the first time in real life! This book is one and a half years old, so it was more than two years in the making. I got into contact with my publishers through Instagram where I was publishing these photographs. It was thanks to Covid really that I managed to take some time to edit all these photos and also to write a text about the deeper meaning of graffiti erasure. And then I got in touch with the guys from Building Books. Although the content of the book is mine, they came up with the format and design. It’s a small book, a lot of people are surprised about it. The publishers and I agreed on most issues regarding the book. They really took the material and ran with it. After the protests, most people in Hong Kong were mentally exhausted by what had happened and so was I. So, it was good for me to pass this material to someone else to work on. We quickly agreed that the book should be focused on the tram stops, as it made a nice consistent series for a book.

In Hong Kong, the old double-decker tram system is owned by a French company and at the tram stops, you get these billboards. During the protests these became a canvas for people to write slogans, and then they were cleaned but not cleaned-cleaned.

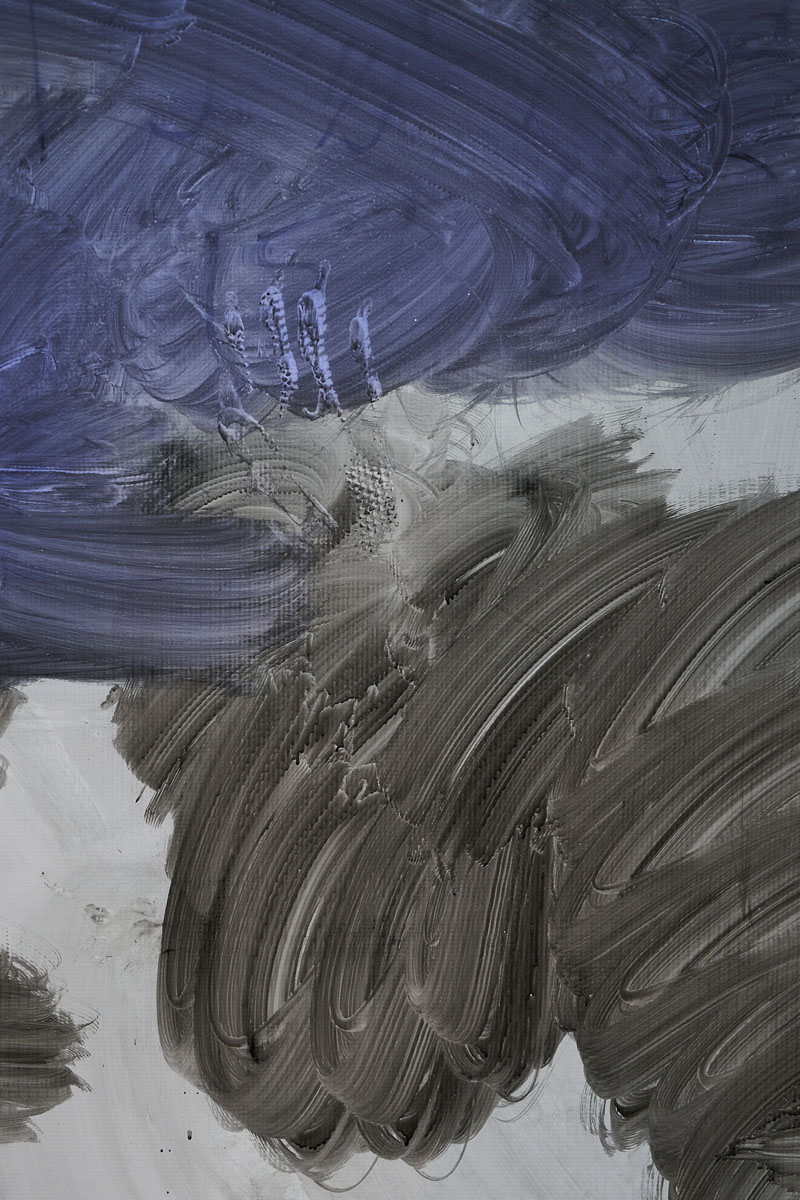

I went to shoot these billboards at night (fig. 11), and you get this nice series because they are all almost the same format, a few next to each other at every tram stop. Really like a triptych or polyptych of paintings like you get in medieval times. It’s a very interesting expressionist formal language, albeit completely unintentional. To me—and I talk about this in the book—this touches on the concept of critical paranoia. As an architect I got interested in this because of Rem Koolhaas, who used this idea from Salvador Dali in his book Delirious New York. Critical paranoia posits that you invest nonsensical or absurd things which intrinsically have no meaning with your own preconceptions, forcing them to make sense. These paintings were created unintentionally, but they became perfect artworks illustrating what was going on in Hong Kong (fig. 12, 13). People in Hong Kong were quite paranoid during this period because of the violence, the government’s double-speak, and continuous rumors swirling around. And I believe that because of this paranoia, people read these erased graffiti as a very poignant representation of what was happening in Hong-Kong. And to me at least, this accidental art was way more illustrative of what was happening than a lot of the intentional protest art, which was often very literal. While a lot of protest art didn’t speak to me (also because of the language barrier), this unintentional art did reverberate with me.

Jordan Hillman: In the text of your book, you frame the failed or abstracted censorship of graffiti in Hong Kong as “inadvertently co-authored by the perpetrators and the agents of the chaos themselves.” Can you say more about what do you mean by this co-authorship?

H. L. Maes: I am always interested in accidental aesthetics happening and the beauty of these erased graffiti is really something that is completely unintentional—it is the result of a funny collaboration between the protestors and the cleaners of the government contractors (fig. 14). What I am doing next is putting together the photos of the different billboards and I am recomposing the whole tram stops in panoramic photos to see them in their totality as they were, an accidental and temporary artwork within the city.