Morts aux vaches: Printing anti-police graffiti in fin-de-siècle Paris

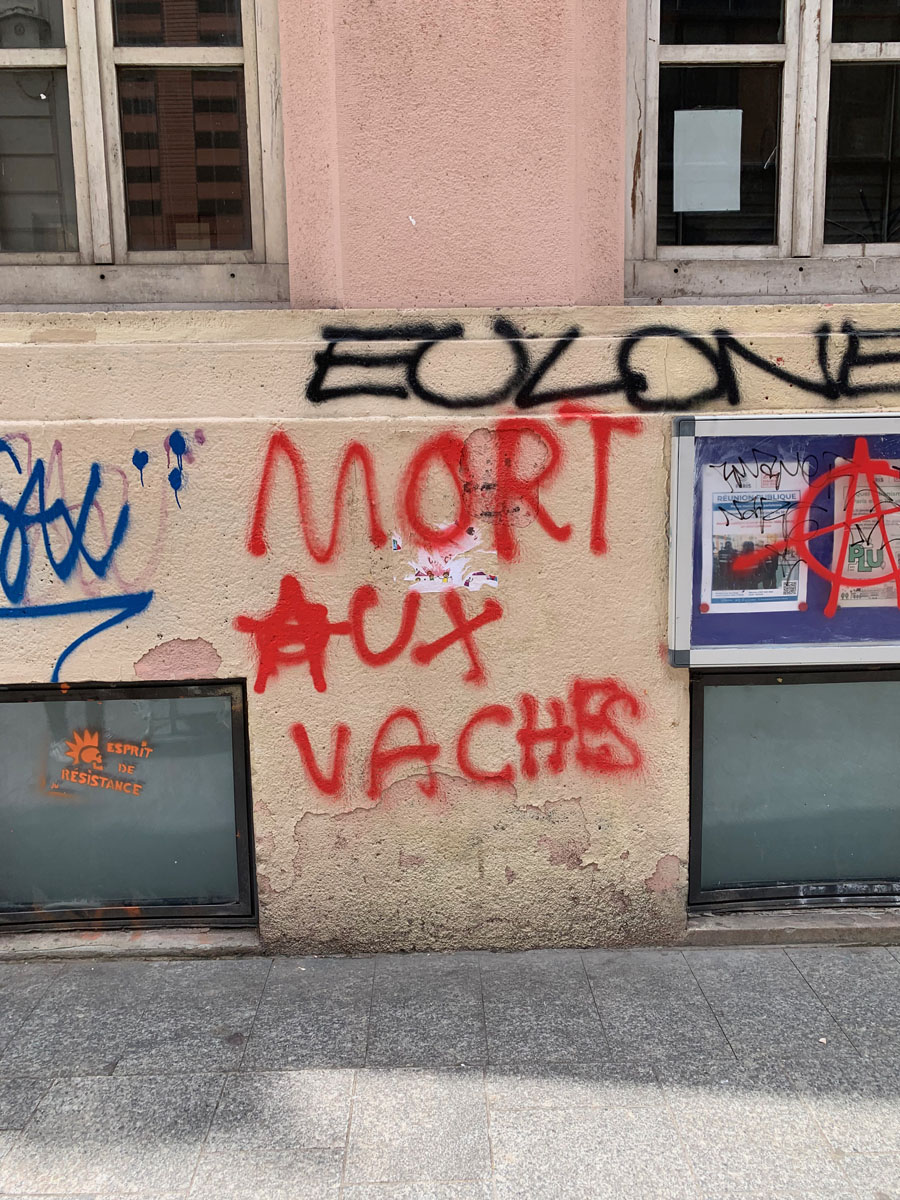

On the morning of June 9, 2022, three words appeared in fresh paint outside the entrance of the Collège Louise Michel on rue Jean Poulmarch in Paris’s tenth arrondissement (fig. 1). Sprayed on the lower portion of the wall, the mass of blood-red block letters evinced the violence of the aspersion they spelled out: “MORT AUX VACHES.” An argotic phrase meaning “Death to cops,” the anti-authoritarian sentiment of the tag was bolstered by the ring drawn around the “A” of “AUX,” which transformed the simple Latin character into the notorious circle-A monogram of the anarchist movement.1

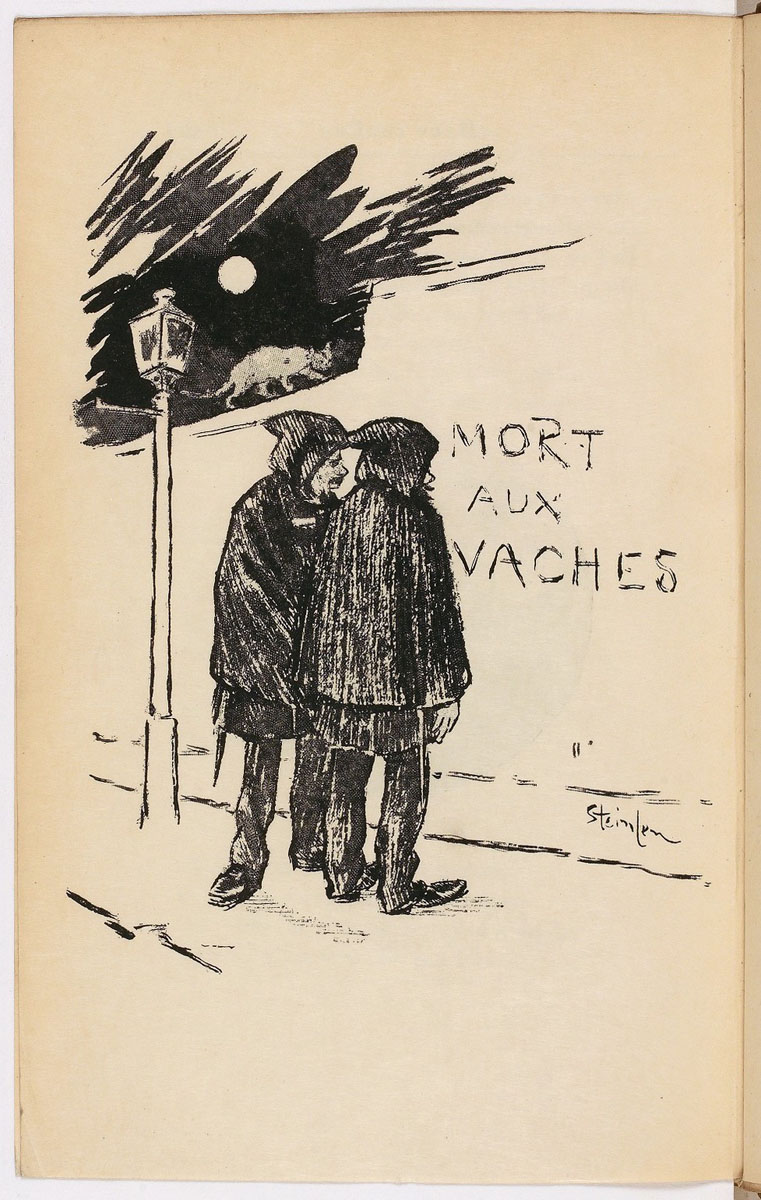

By the following day, the anonymous message was gone, covered over as part of the capital’s aggressive municipal campaign of urban maintenance.2 Yet, as the photograph attests, the erasure was ultimately incomplete: rather, the tag’s seeming ephemerality was converted to permanence through its photographic capture and circulation. In late-nineteenth century Paris, printmakers sought to do the same by appropriating graffiti as an expressive—and resistant—mode in their illustrations of the street, with mort aux vaches dominating their imagined inscriptions (fig. 2). This politicized expression, already associated with anarchism by the 1890s, was scrawled on the spaces of the pictorial city by fin-de-siècle artists, notably Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen and Auguste Roubille.

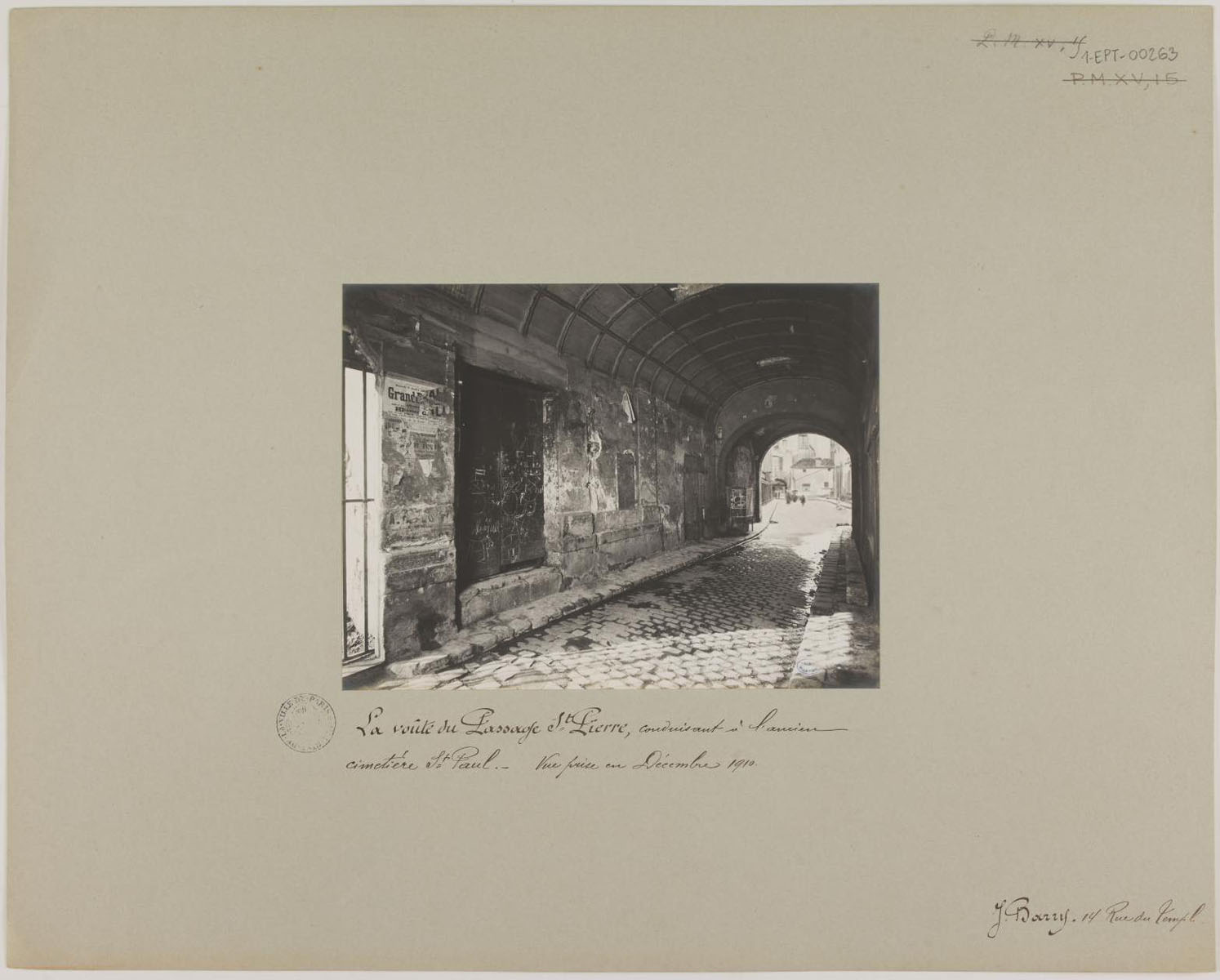

In their graphic graffiti, these draftsmen used hand-drawn majuscules akin to those written on rue Jean Poulmarch, but contrary to the contemporary example, the medium deployed was not paint. Rather, like the prints themselves, which were born of plate and ink, the inscriptions, too, registered an incisive process of graffiti writing. The word graffiti comes from the Italian sgraffiare, literally meaning “to scratch,” and at the turn of the twentieth century, incised graffiti was not unusual in Paris (fig. 3). As historian Elizabeth Sage has shown, etching was, in fact, one of many methods of fin-de-siècle graffiti writing that also included chalk, pen, pencil, paint, and written or mechanically printed texts that could be pasted onto walls or other surfaces in the city.3 This range of practices determined the visual impact and audience for the messages of graffiti writers, but also the difficulty of their removal.

Today, Paris’s graffiti removal program consists of an extensive system of municipal agencies and private contractors, but in the late nineteenth century, it was the police who were called upon to document and efface “unofficial” inscriptions in the capital.4 At two-thirty in the morning on January 1, 1880, for instance, M. Mouguin, a peace officer on patrol, was drawn to a crowd forming on a sidewalk in the second arrondissement. As he described in his nightly incident report, “Passers-by stopped at rue des Jeuneurs, 26, to read the following inscription, written in chalk on a storefront: ‘Mort aux vaches et aux sergents de ville.’ Officer Mouguin covered this inscription using a sponge and the curious withdrew. Mr. Thomas de Colligny, Commissioner of Police, has been informed.”5 The ease with which Mouguin was able to efface the insult was determined by the writer’s choice of medium: chalk. As an inherently impermanent material, chalk would inevitably degrade and disappear by the impact of the elements alone. It was not a message designed to last in the way that one carved into the stone or wood of the storefront might. Yet, like the photograph at the outset of this essay, the policeman’s encounter with and erasure of the expression ironically meant the documentation and preservation of its message for posterity.

Moreover, reports like Mouguin’s affirm the reality of graffiti as a practice of urban resistance in late nineteenth-century Paris, one that often sought to challenge the forces of order in the primary space that they occupied: the street. The message on rue des Jeuneurs, for example, was clearly meant to confront its subject—the police—and to pose a direct challenge to the dignity of their force, whose responsibility it was to maintain order in the city. Its erasure by police, then, was not only an attempt to curb the potency of the outcry, but also to prevent a crowd from rallying around it.

Yet, as urban theorists have shown, the modern street remained a site of active resistance despite State efforts to regulate for what and by whom it should be used. In fact, Michel de Certeau explains in The Practice of Everday Life, it is by “mak[ing] different use” of the street’s constraining features that those very constraints are most effectively subverted:

If it is true that the “grid” of discipline is everywhere becoming clearer and more extensive, it is all the more urgent to discover how an entire society resists being reduced to it, what popular procedures (also “miniscule” and quotidian) manipulate the mechanisms of discipline and conform to them only in order to evade them, and finally, what “ways of operating” form the counterpart, on the consumer’s (or the “dominee’s”) side, of the mute processes that organize the establishment of socioeconomic order.6

In other words, de Certeau suggests that by resisting or manipulating the sanctioned uses and authoritative structures of the street, one can, “without leaving the place where he has no choice but to live and which lays down its law for him, establish within it a degree of plurality and creativity” and find alternative “ways of operating” that elude the dominant social and political order, even if only partially or temporarily.7

For Henri Lefebvre, it is this potential for spontaneity and disorder that makes the street so dangerous to those in power and so attractive to those without. “The street is disorder,” Lefebvre writes. “All the elements of urban life, which are fixed and redundant elsewhere, are free to fill the streets and through the streets flow to the centers, where they meet and interact, torn from their fixed abode. This disorder is alive. It informs. It surprises.”8 He continues,

In the street and through the space it offered, a group (the city itself) took shape, appeared, appropriated places, realized an appropriated space-time. This appropriation demonstrates that use and use value can dominate exchange and exchange value. Revolutionary events generally take place in the street. Doesn’t this show that the disorder of the street engenders another kind of order?9

According to Sage, this “other kind of order” is one in which the street’s various users—pedestrians, workers, schoolchildren, peddlers, prostitutes, and their pimps— “can do, behave, speak, and write in impudent, audacious, disrespectful, brazen, and defiant ways that those in power would prefer to eradicate.”10

Regarding language as a tool of resistance, Lefebvre characterizes the urban space of the street as, “a place for talk, given over as much to the exchange of words and signs as it is to the exchange of things. A place where speech becomes writing. A place where speech can become “savage” and, by escaping rules and institutions, inscribe itself on walls.”11

This idea resonates with the fin-de-siècle usage of mort aux vaches, which was employed as both a verbal and textual affront to the forces of order. While the tone of the spoken insult could add to its injury, the written form was able to physically impress itself onto the ordering systems and structures it sought to upend.

Through the work of Steinlen and Roubille, mort aux vaches also became a pictorial insult, mobilized in their prints through an interplay of word and image. The subversive potential of the message and medium to disrupt dominant urban order was clearly recognized by these artists, whose work focused on Paris’s marginalized populations, including laborers, sex-workers, and criminals. It was largely to members of these so-called classes dangereuses that the phrase mort aux vaches appealed as a means of sociopolitical resistance, and Steinlen and Roubille, both of whom were affiliated with the anarchist movement, were particularly sympathetic to their plight.12

This essay argues that the use of mort aux vaches was both an act of solidarity with the lower classes and a means of resistance for these artists, who—like actual graffiti writers in the streets—sought to challenge the inequities of the dominant bourgeois order of the Third Republic through their work. Their adoption of mort aux vaches as a pictorial device pushed against nineteenth-century discourse that linked socioeconomic status and criminality and championed the related incisive forms—printmaking and graffiti—as effective means disrupt it. Frequently published in anarchist, satiric organs of the press, their prints were also encountered in the streets, sold on the kiosks that populated nearly every corner of the capital. Moreover, in their writing of the words into the image, Steinlen and Roubille mimed the role of graffeur in print: juxtaposed with the typographical text of the captions or lyrics, the inscriptions called attention to their seemingly hand-written nature. Yet by translating mort aux vaches into a reproductive medium, they also recovered the permanence lost in the more transitory forms of urban writing popular in fin-de-siècle Paris. Like the photograph or the police report, then, mort aux vaches as a motif in print functioned to not only preserve the message, but also to propagate it.

Pourquoi vaches?

Though generally associated with anarchism, the genesis of mort aux vaches as an insult to authority does not date to the ère des attentats (1892-94), when attacks in Paris brought their radical movement against hierarchical government and authority to the fore.13 In fact, some scholars have traced its usage as far back as 1590, when Henri IV’s troops besieged the city under banners that allegedly bore an image of two cows, prompting Parisians to formulate the taunt. More often, the derogatory expression has been understood as a phonetic slippage born of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). During the conflict, the German guard posts along the border between the two countries were inscribed with the word “Wache,” meaning guard or sentry. The French, who pronounced the “w” as a “v” in their native tongue, thus incorrectly threatened their enemy with cries of “Mort aux vaches.”14

Inadvertently, this mispronunciation produced a homonym in French—vache, meaning “cow”—which proved to be a potent subversive device easily mobilized across verbal, textual, and visual fields. And, given that before the Franco-Prussian War the noun vache was either absent from argotic dictionaries (of which there were many) or defined alternatively as “a woman of bad morals” or “a man without courage,” the 1870 provenance of the phrase seems most plausible.15 But regardless of whether it originated in the sixteenth or the nineteenth century, mort aux vaches was decidedly rooted in an active resistance to the prevailing forces of order, a resistance that was, by the 1880s, logically extended to the police as the predominant authority in Paris.

Still, it was not until Charles Virmaître’s 1894 Dictionnaire d’argot fin-de-siècle that vache officially acquired the definition of “city sergeant or safety officer” in the popular lexicon.16 By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, Aristide Bruant’s L’Argot xxe siècle. Dictionnaire Français=Argot (1905) and Napoléon Hayard’s Dictionnaire Argot-Français (1907) had done away with all significations of vache apart from “any agent of the police.”17 In Virmaître’s entry, however, the lexicographer went beyond a simple definition to locate the word as belonging to a specifically criminal vocabulary. He wrote:

In the prisons, despite regulations and the active surveillance to enforce them, the detainees write their thoughts on the walls. The most common are the following:/ —Mort aux vaches. /— Quand je serai désenflaqué, gare à la vache qui m’a fait chouette et qui m’a fait tirer un bouchon (Argot des voleurs).18

In other words, Virmaître associated the phrase mort aux vaches by definition both with graffiti writing as an act of defiance and with incarceration.

More than a decade earlier, on February 14, 1881, the Catholic daily journal L’Univers had published a letter addressed to its editor by the politician Henry Cochin, who had recently been released from the Prison de la Santé.19 In detailing his experience as an inmate, Cochin devoted a section of his letter to the graffiti on the prison’s courtyard walls, which stated in part, “Everywhere we read this curse: ‘Mort aux vaches!’ The cows are the police officers.”20 Cochin’s recollection thus suggests that the phrase had been linked to criminality long before Virmaître.

Indeed, mort aux vaches was inscribed not only on the walls of prisons but on the prisoners themselves.21 In the chapter on tattooing in his 1885 Les Propos du docteur : médecine sociale, hygiène générale à l’usage des gens du monde, Dr. Ernest Monin explained:

Today we can say that the tattoo is the clothing of savages and criminals…[It] plays a certain role in the history of crime. Our readers have seen it, on the occasion of the recent death sentence. “Mort aux vaches” (cows meaning, in convict slang, the representatives of the police): such was the interesting motto borne, indelibly, by the young Meerholz, known as the “Pacha de la Glacière,” which justice will soon deliver into the skillful hands of Mr. Deibler.22

Articles published about Meerholz, the nineteen-year-old gang leader convicted of murder on September 30, 1884, emphasized that his “full body is covered in tattoos of grotesque figures and inscriptions.”23 In L’Intransigeant, for example, it was noted that he has “on his left leg, a gendarme, under which it is written: Death!”24 Le Petit républicain de la Haute-Garonne went so far as to compare Meerholz’s body to that of “an Indian chief. We read on his right arm the word: ‘Pacha,’ on his left arm is a design of a fish under which one finds the words: ‘François, say Mort-aux-Vaches !’”. From these tattoos, the journal concluded that “Meerholz must not, in fact, have a great fondness for the gendarmerie. He spends his time on the run from them to hide the thousand and one misdeeds on which he lives.”25 In other words, Meerholz’s tattoos functioned as personal graffiti, transforming his body into a living support for the outward expression of his defiance against order and authority.

Outrages aux vaches

The deployment of mort aux vaches against the forces of order was itself criminalized under French law. However, as Édouard Fuzier-Herman, Adrien Carpentier, and Georges Frèrejouan du Saint explained in a section of their Répertoire général alphabétique du droit français entitled “Anarchist Propaganda,”

One cannot classify among the seditious cries, those of: À bas l’armée ! À bas la gendarmerie ! Enlevez les agents ! Mort aux vaches ! etc. They undermine, it is true, the prestige of the army, of the agents of the public force; but they do not provoke the overthrow either of the Government of the Republic or of the public authorities; they can therefore only be considered as insults to those against whom they are directed.26

Mort aux vaches was not considered legally “seditious” but rather belonged to a particular category of prosecutable insults known as outrages, discussed at length by Elizabeth Sage elsewhere in this volume. According to her, an outrage is defined as a “word, gesture, or threat, written or drawn, attacking the dignity or the respect due to an agent of the public force in the exercise of his or her functions.”27

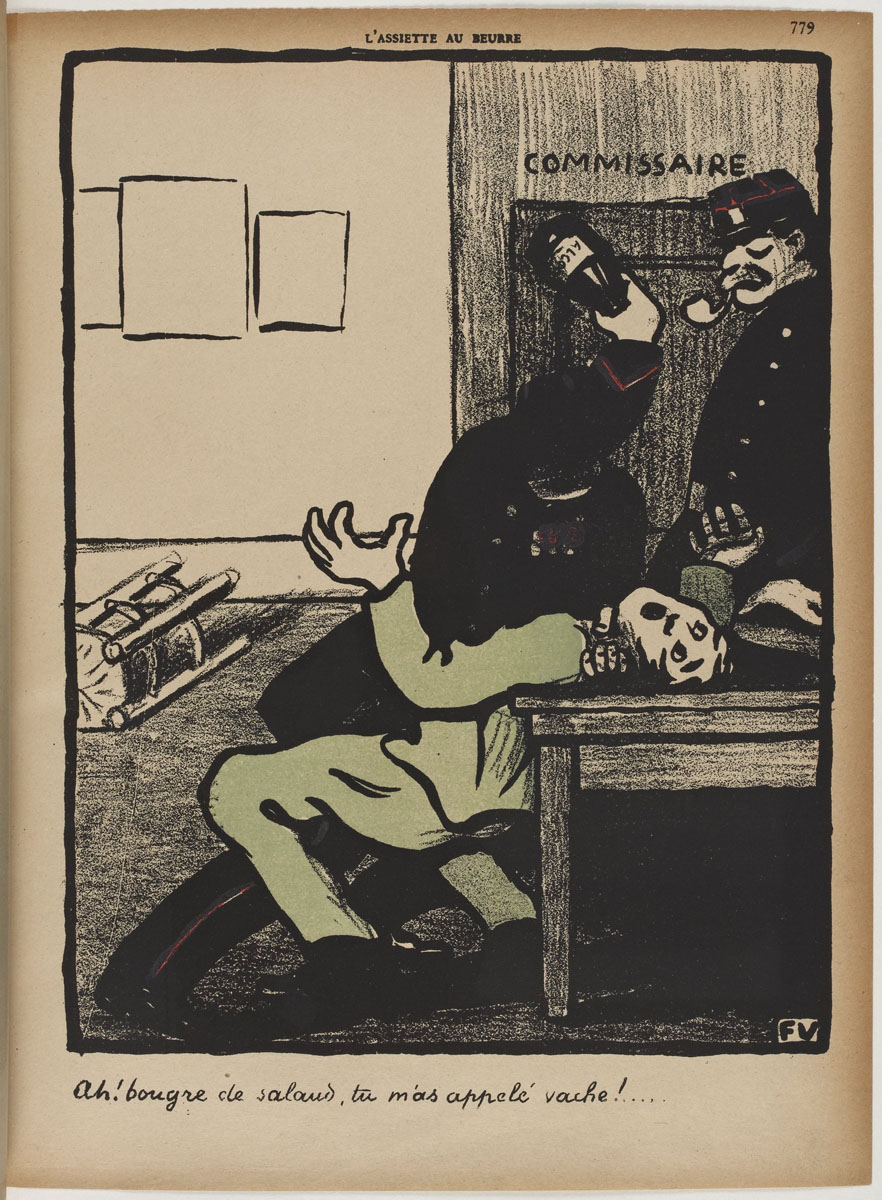

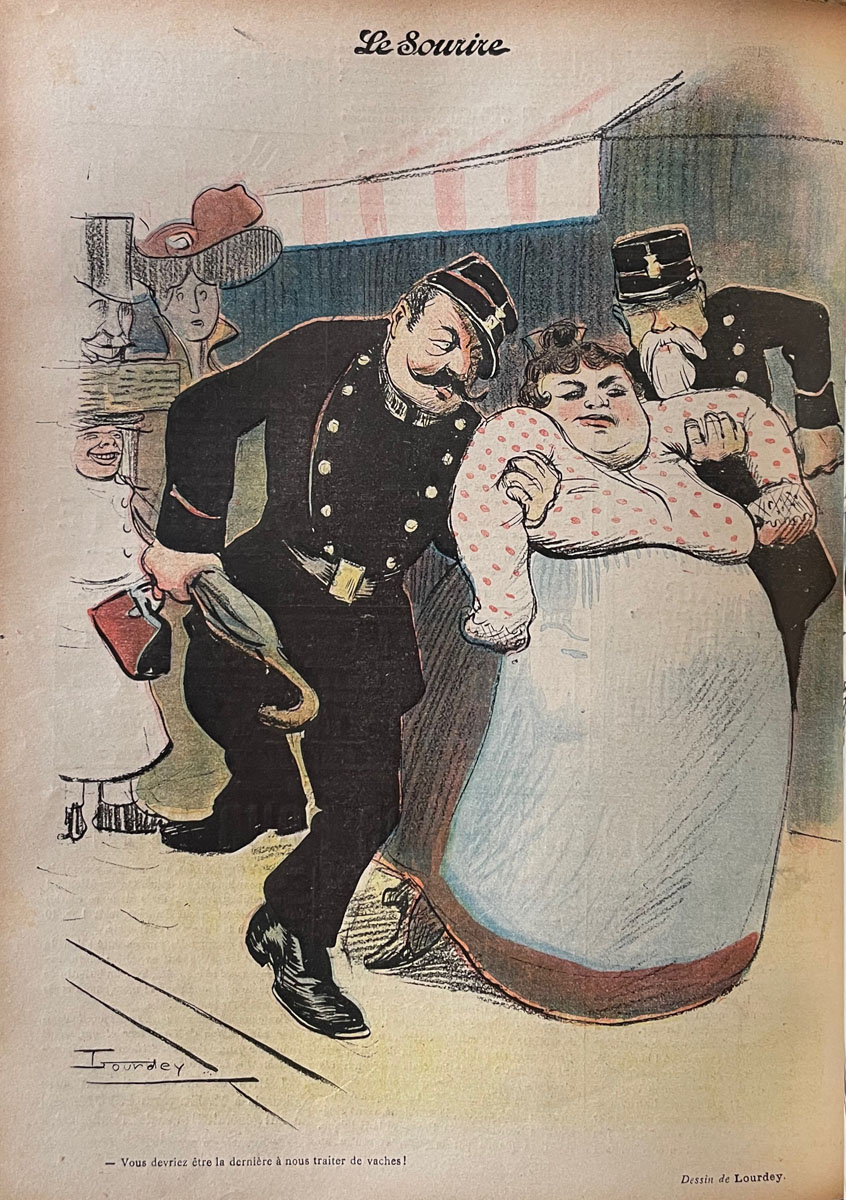

Illustrations published in satirical journals at the turn of the century highlight the potential of mort aux vaches to undermine the authority of the police and the show of authority it seemingly necessitated in response. One by Félix Vallotton for a special issue of L’Assiette au beurre entitled “Crimes et châtiments,” for example, shows an officer beating a man with a wine bottle inside the Commissaire for “having called [him] a vache!” (fig. 4).28 In another by Lourdey, which appeared in the humorous Le Sourire in June 1900, two officers take a heavy-set woman into custody, chiding, “You should be the last one to call us vaches” (fig. 5).29

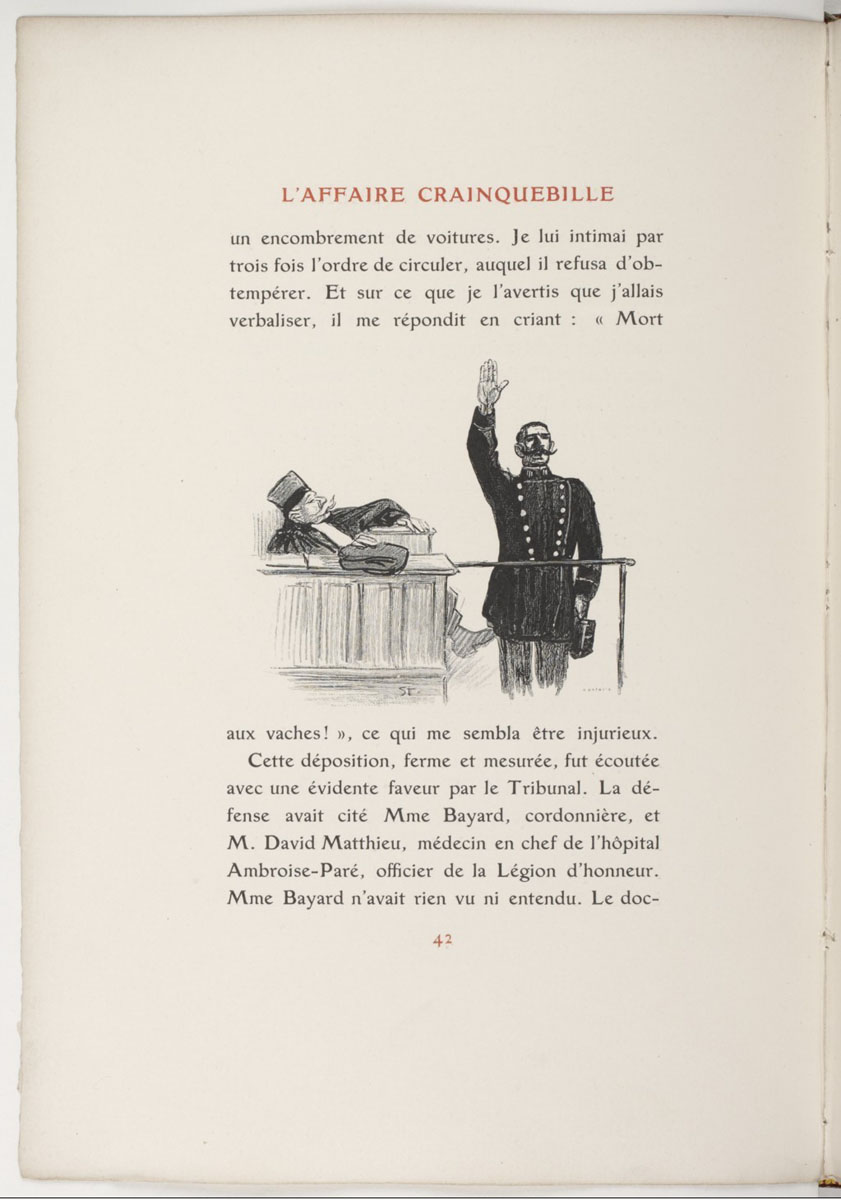

This outrage was also at the center of Anatole France’s L’Affaire Crainquebille, a novella illustrated by Steinlen in 1901. In it, Crainquebille, an ambulant vegetable seller, is arrested after a verbal misunderstanding with Constable 64 on the rue Montmartre, who amid the chaos of the afternoon rush believes the costermonger insulted him with the derogatory slur mort aux vaches. Crainquebille insists that he had said no such thing, but it does not matter. He is brought to trial where the police officer testifies against him and the judge takes the officer’s word as fact, recognizing that “to ruin the authority of Constable 64 is to weaken the State.”30 As a result, the costermonger is sentenced to two weeks in prison, initiating a downward spiral that ultimately leads to his suicide.

In L’Affaire Crainquebille, a consistent failure of language, from the initial moment of confusion to the incomprehensible legal jargon of the court, corrupts communication between the citizen and the justice system. Steinlen’s courtroom illustration mimes this breakdown by positioning the vignette on the page to disrupt the very phrase Crainquebille is accused of having uttered (fig. 6). The textual split between “Mort” above and “aux vaches !” below reflects the interruption of communication and justice that ultimately condemns the costermonger. This is reinforced by Steinlen’s rendering of the courtroom actors: the lackadaisical attitude of the judge, communicated by the informality of his posture, contrasts sharply with the rigidity of the officer, who stands upright with his arm powerfully extended in sworn testimony, a contrast taken further in the drooping white mustache of the magistrate versus the dark, upturned mustache of Constable 64.

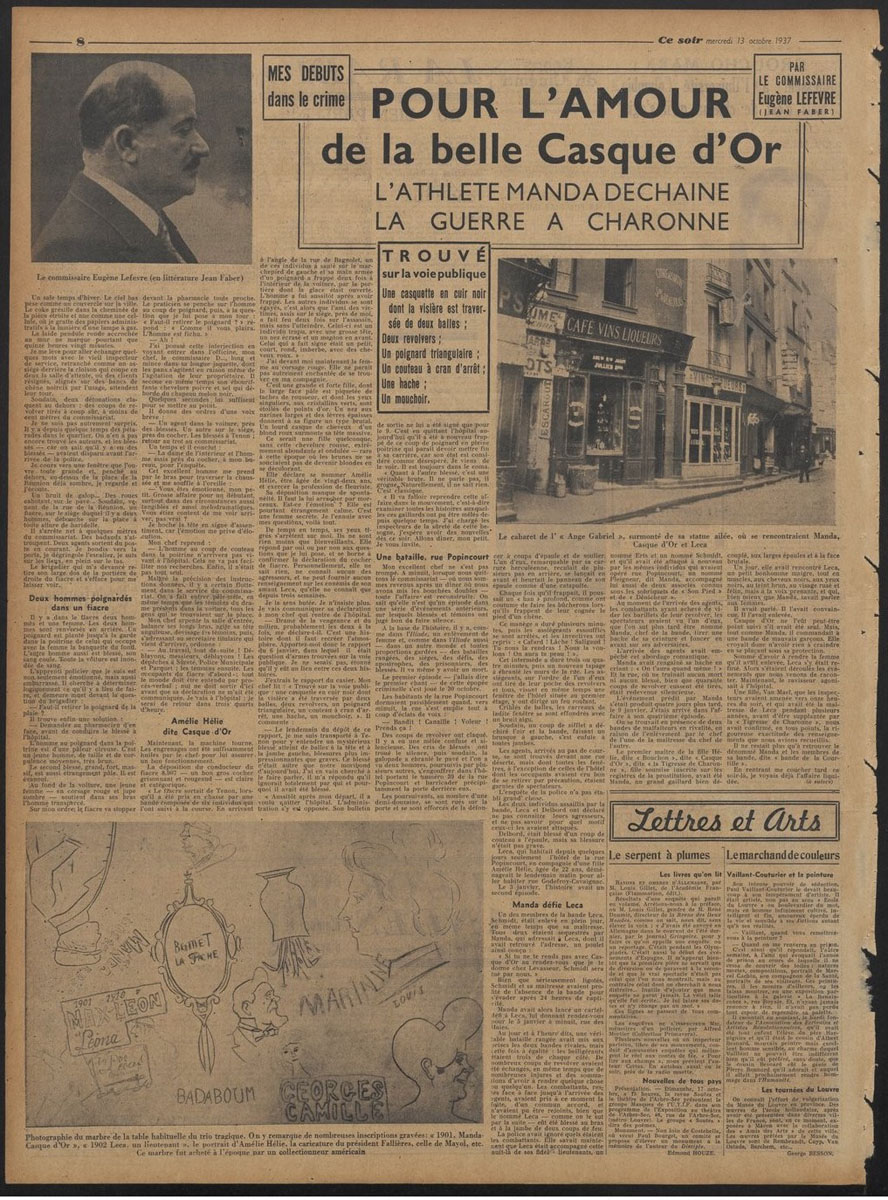

Though a loose parody of the ongoing national drama of the Dreyfus Affair, which likewise revealed the failings of the French judicial system and the severe impacts of its carelessness, France’s narrative was also closely linked with more quotidian affaires involving the use of mort aux vaches.31 On December 13, 1900, for instance, Leon Roux recounted an incident that occurred between Frédéric Vogt, an Alsatian pastry chef, and police officers during a demonstration in Paris in his column entitled “Autour du Palais. Le petit pâtissier” for La Revue des tribunaux :

City sergeants claim that the little pastry chef shouted: “Mort aux vaches! Mort aux vaches!” (“Vache” is taken here, in a disparaging sense for policemen and unflattering for the mothers of our calves!)

—I did not insult the agents, protests Frédéric Vogt. There is, I know very well, some enmity between the sergents de ville and the young members of the French patisserie. But during the demonstrations in favor of Mr. Krüger, my guild did not have to complain too much about the police. I shouted: “Arbitrage! Arbitrage!” and not anything else.”32

In court, M. Vogt argued that it was his Alsatian accent that was responsible for the unfortunate miscommunication, but like the fictional Crainquebille, he was found guilty and sentenced to eight days in jail.

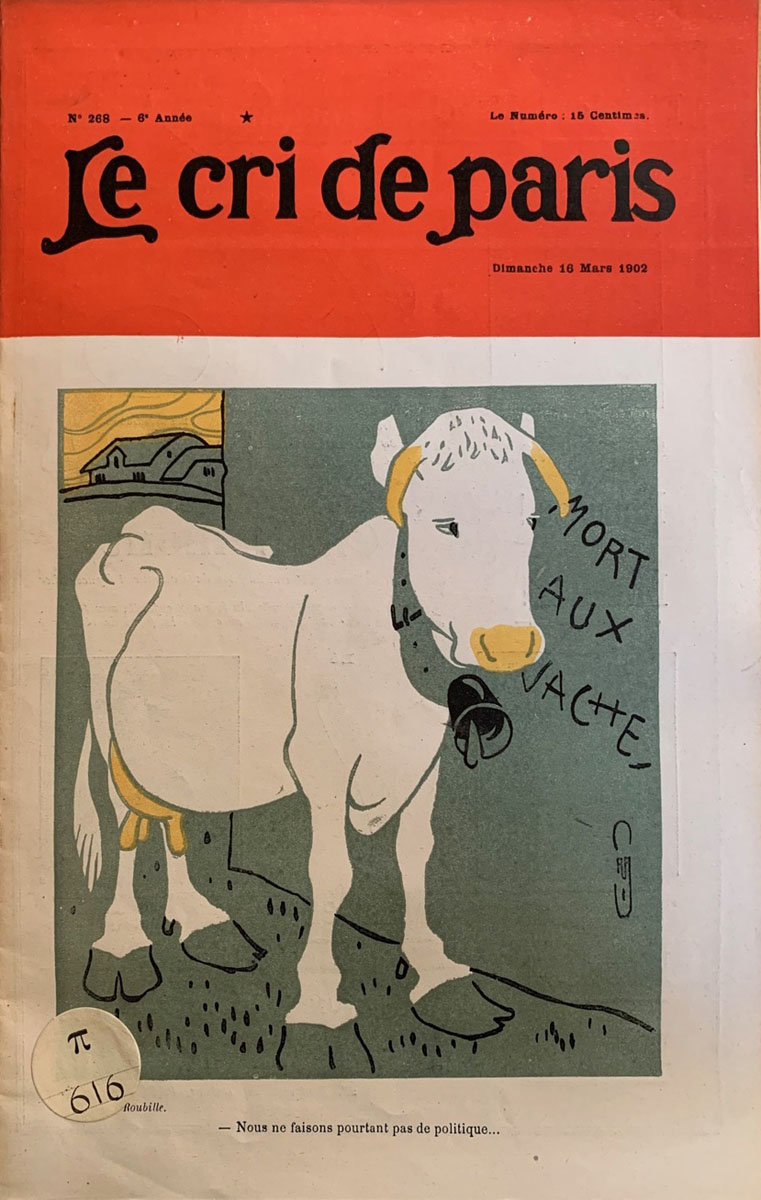

Roux’s quip that the association of the word vache with policemen was “unflattering for the mothers of our calves” was taken up in a design by Roubille for Le Cri de Paris (fig. 7).33 On the cover of the March 16, 1902, issue, the artist shows a vache, the bovine species, at home in an expansive pastoral landscape of sage grass and amber sky. From the lower right corner, the wall of an outbuilding cuts diagonally into the scene, the words “Mort aux vaches” scribbled at an angle in black. The hateful inscription catches the grazing cow’s eyes, her heavy lids seconding the melancholy of her response, “We don’t do politics…”34.

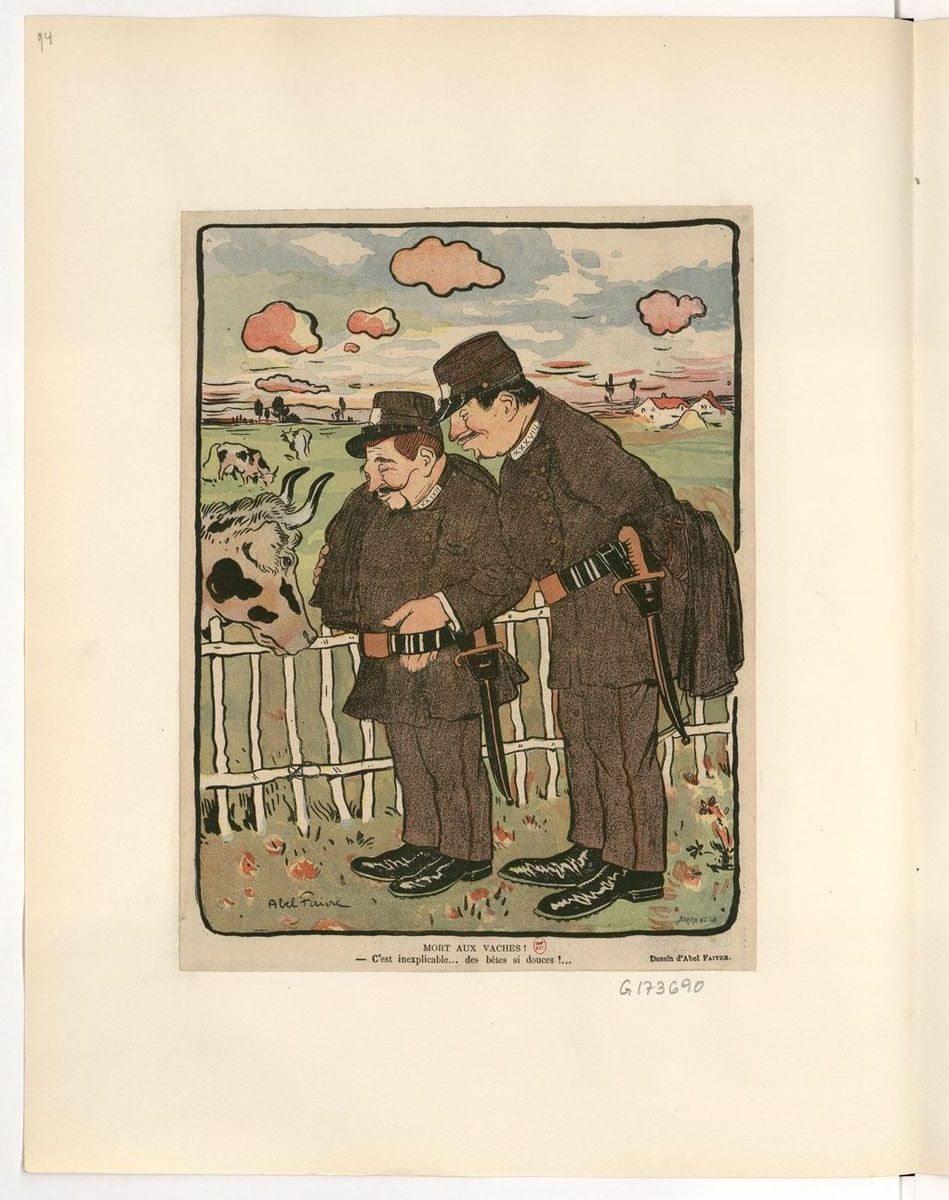

Despite Roubille’s use of graffiti in this image, which places mort aux vaches in a seemingly self-evident textual form, the ambiguity of language persists. As with Crainquebille and Vogt, the intended message is lost in translation, disrupted by the displacement of the expression from the urban landscape to the rural, where the presumed target—the police—is not present. In this new context, the word vache sheds its argotic signification and returns to a literal sense of the phrase—death to cows—which is the certain conclusion of the agricultural system to which this animal belongs. Even when the police are placed into this rural context, as in Abel Faivre’s design for Le Rire, the misunderstanding persists, as the officers ponder why anyone would wish mort aux vaches upon such gentle beasts (fig. 8).35 These satiric illustrations point to the decidedly urban resonance of both argot and graffiti as communicative modes, modes whose disruptive potential required the backdrop of city streets for their legibility.

Dans la rue

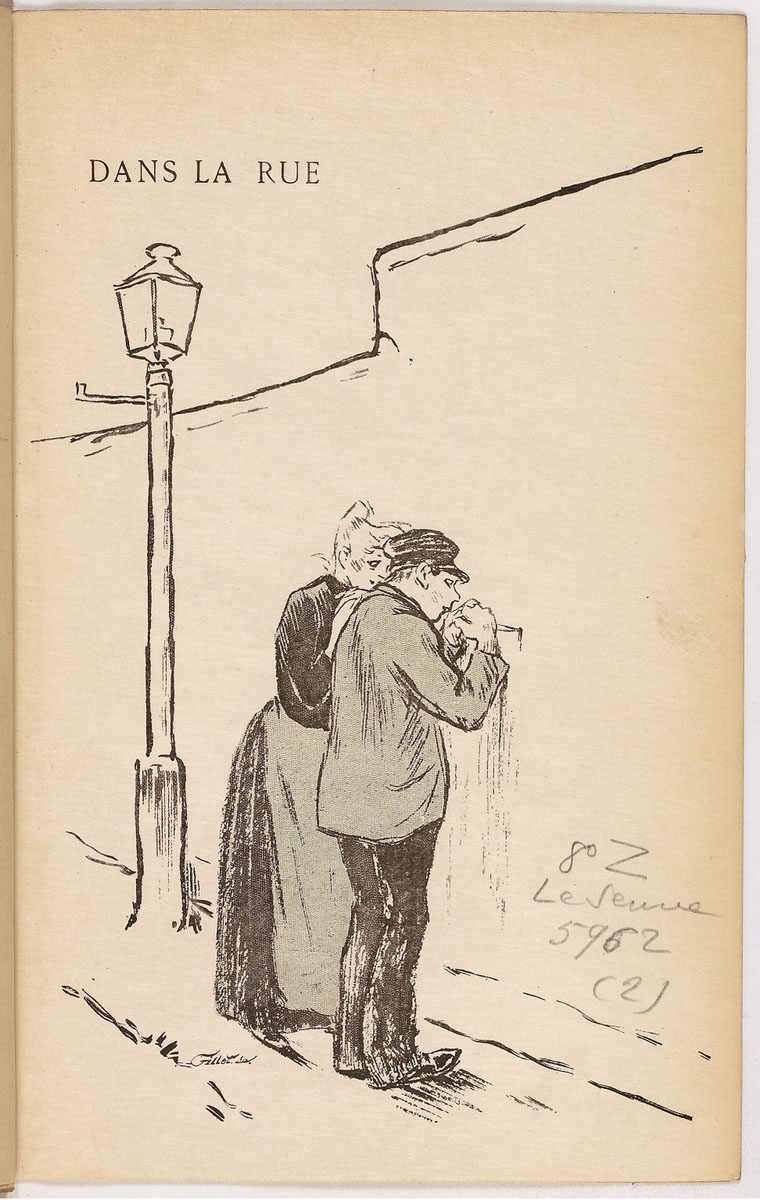

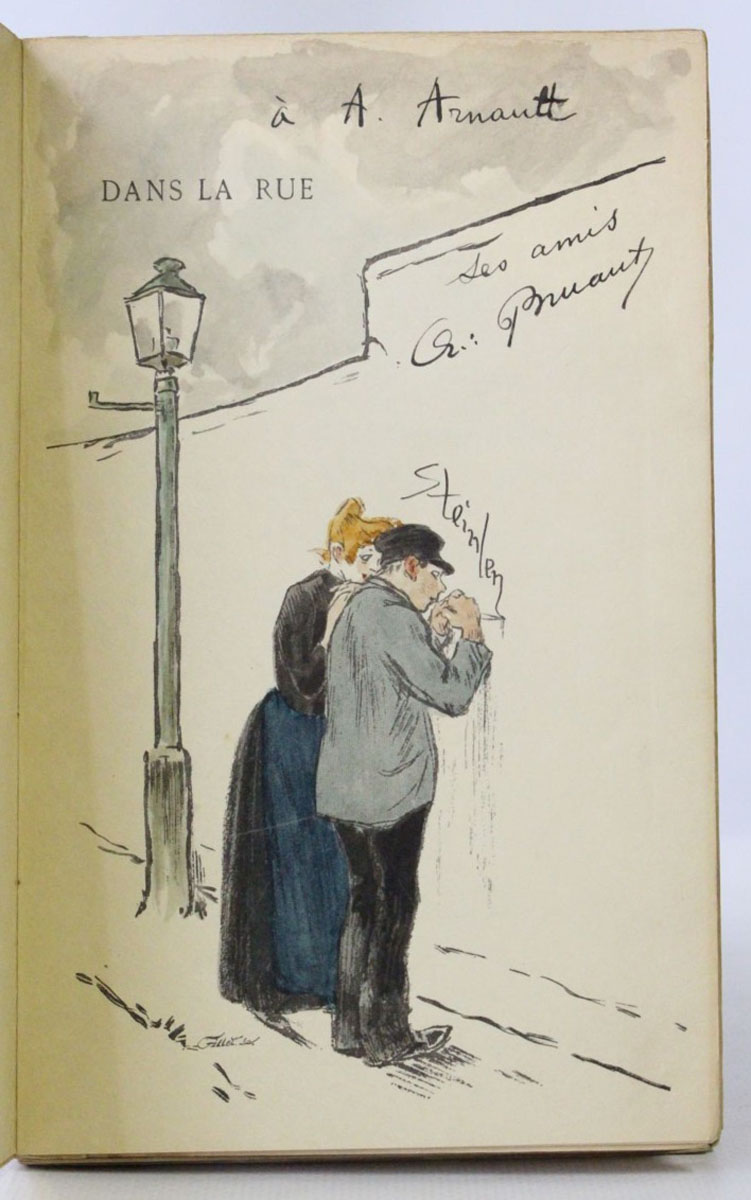

Steinlen’s collaboration with Aristide Bruant on his second collection of songs and monologues in 1895 highlights the interplay of argot, graffiti, and printmaking as acts of urban resistance. In the volume, aptly titled Dans la rue, Steinlen and Bruant introduced a synergistic program of word and image that immersed the readers in the lives of Paris’s most downtrodden inhabitants.36 The singer’s argotic verses were seconded by over one hundred of Steinlen’s abbreviated designs, which overlapped and integrated with the text and the music and served as either vignettes or separate full-page illustrations.37

The second volume of Dans la rue opens with a frontispiece by Steinlen that shows a proletarian couple tagging a city wall (fig. 9). A man in his worker’s smock begins to carve as his female companion keeps watch. On the final page, we see the fruits of their labor as two officers on night patrol in Paris pause to inspect the graffiti which reads mort aux vaches (fig. 2). Steinlen’s placement of the inscription beneath a streetlamp—the twinned sentinel of the police in fin-de-siècle Paris—reiterates the futility of infrastructural and legal efforts to control urban space.38

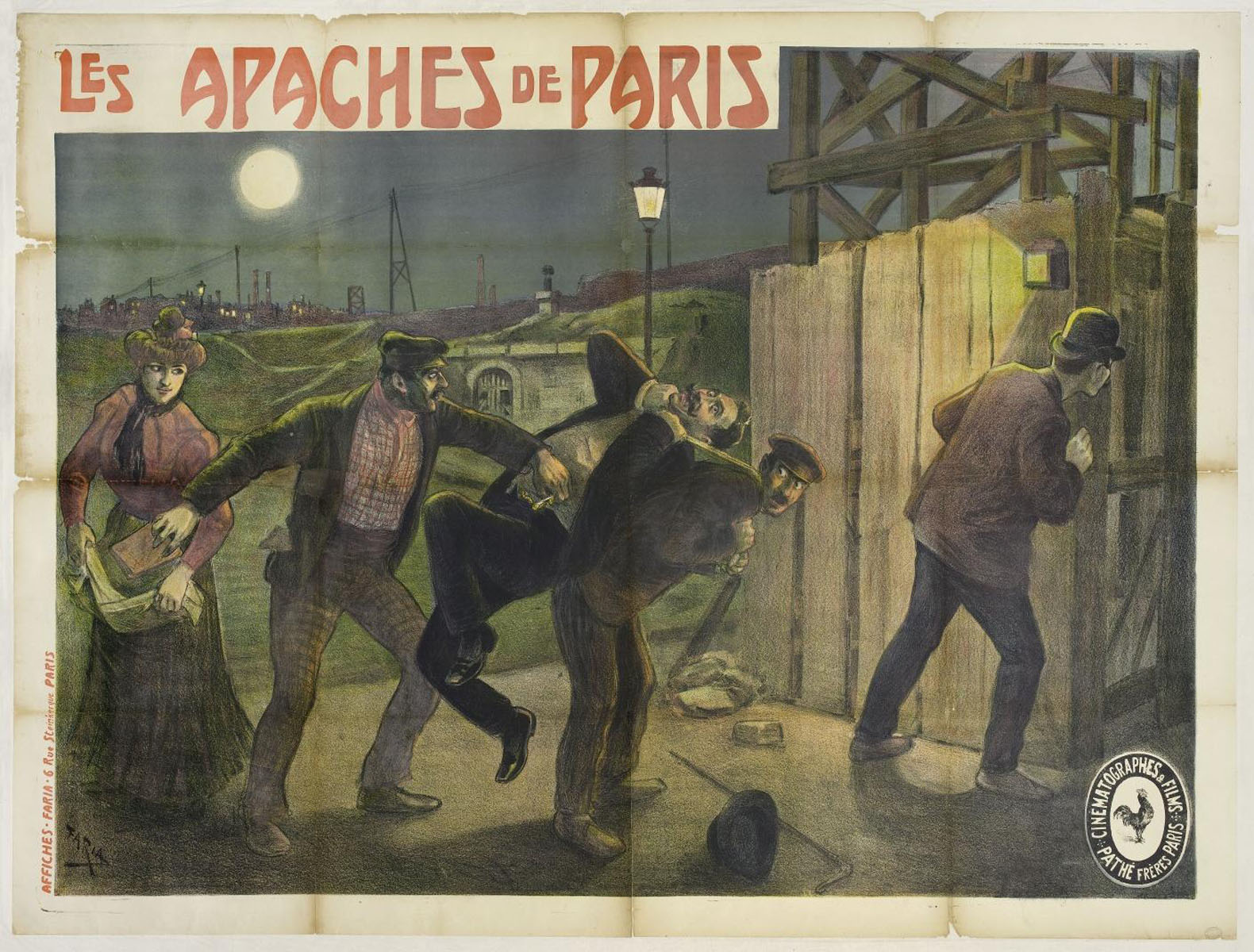

It is clear from a comparison of Steinlen’s frontispiece with photographs and illustrations from the period that the two graffeurs in the print are apaches, a turn-of-the-century designation that referred to the young thugs of the French capital.39 Aged fifteen to twenty, these “Parisian Indians” came from the urban underclasses in the poor districts where they lived in mixed bands and resorted to crime—especially theft and prostitution—to survive.40 In Steinlen’s rendering, the hairstyle of the young woman, for example, is reminiscent of the Casque d’Or, Amélie Hélie, a “celebrated gigolette” who was the muse and co-conspirator of Manda and Leca, leaders of a band of apaches in northeastern Paris around 1900 (fig. 10).41 Beyond their petty crimes, the trio was even known to write graffiti; for instance, they inscribed self-portraits, political caricatures, and text into the marble of their usual table at the cabaret they frequented (fig. 11).42 A similar female likeness is shown in Candido Aragonez de Faria’s affiche for Pathé’s film Les Apaches de Paris of 1905, accompanied by men wearing the typical slouchy caps and unbuttoned flannels of the emergent criminal type (fig. 12).43

In Bruant’s monologues, as in life, these marginalized figures are shown to be actively targeted by the police with few resources at their disposal. Beyond such legal prejudice, his lyrics and Steinlen’s designs describe the street as a site of uneven commercial exchange: peddlers push their wares, prostitutes sell their bodies, and vagabonds beg for alms, all proletarian means of survival dictated by the demands of the bourgeois consumer and dependent on the cooperation or ignorance of the law. And while certain characters fall prey to the system, others use its infrastructure to actively resist it. This is especially apparent in Steinlen’s full-page designs that bookend the volume, which illustrate how graffiti writing—though not the only source of text or rebellion in the city—offered the possibility of subversion to even the most vulnerable figures dans la rue.44

The practice of graffiti writing to manipulate the dominant order of the street is one in which the artist saw himself as participating. In addition to the mass-produced copies of the songbook, Steinlen and Bruant published a limited edition of 150 numbered examples that contained unique dedication pages rendered in watercolor rather than engraving. In A. Arnault’s copy, numbered 130, the frontispiece has been significantly altered: the message of insult previously inscribed on the wall is replaced by the artist’s signature (fig. 13). We see the male figure carving the final flourish on the letter “n,” casting Steinlen himself in the role of the apache-graffeur.

In the mass-produced volumes the incisive method used to produce the letters on the wall invokes the process of printmaking itself, whose infinite reproducibility makes the act of erasure challenging if not impossible. The actual technique for producing the image in this case—watercolor—instead returns Steinlen’s graffiti writing back into singular form, meant for a particular set of eyes at a particular moment. Yet even in the limited edition, the final image shows officers assaulted by the graffiti mort aux vaches. Thus, Steinlen’s alignment of himself with the apache-graffeur from the outset of the text confirms him as the author of mort aux vaches, too. In so doing, he mobilizes the subversive potential of the rue—the literal urban space, its visual representation, and Bruant’s text, Dans la rue—to engage in an artistic act of resistance. The uneven lettering of mort aux vaches, which is differentiated from the standard typography throughout the volume, serves as a further trace of Steinlen’s hand in its production.

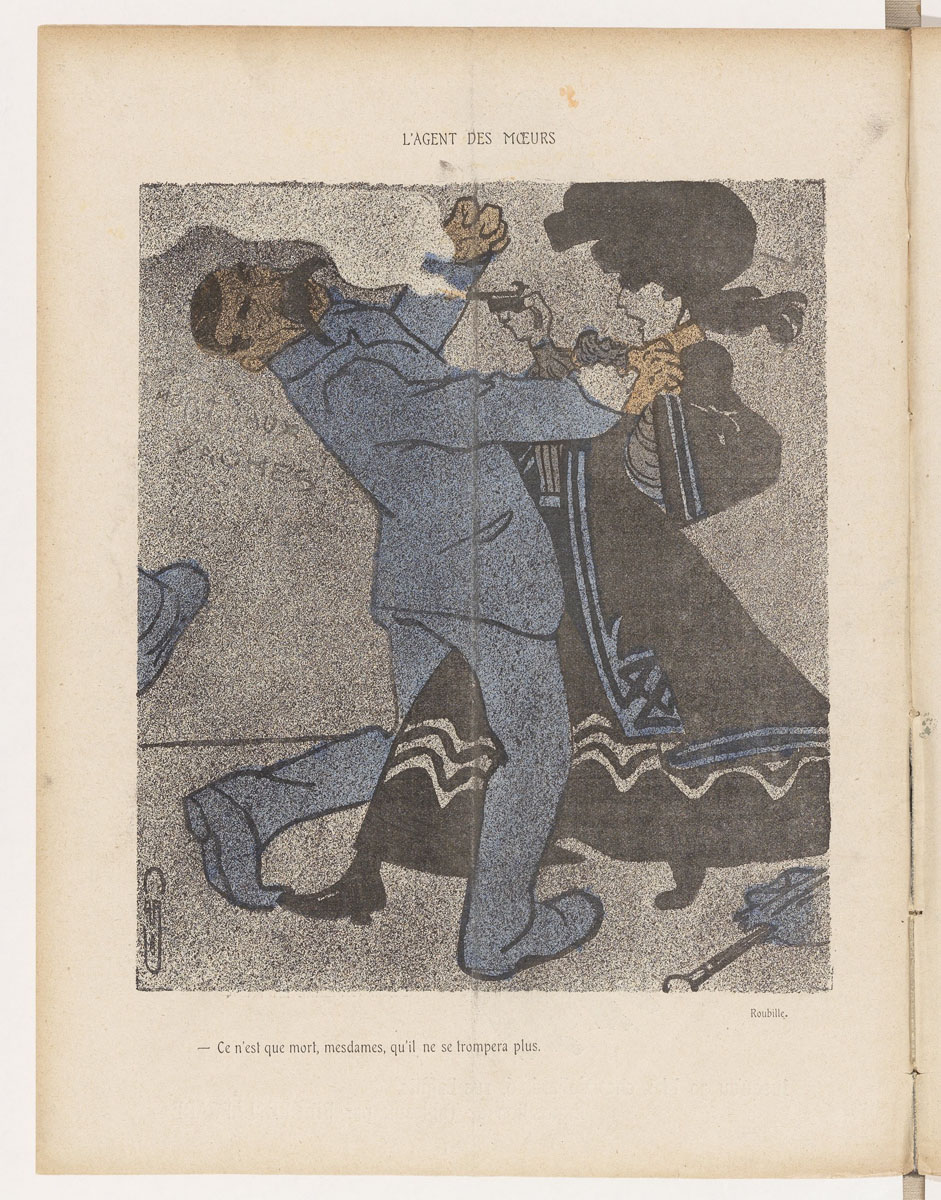

The same might be said of Auguste Roubille’s 1903 illustration, “L’Agent des mœurs,” published on the back page of an issue of Le Canard sauvage for which Steinlen had contributed the cover (fig. 14). This number of the short-lived satiric journal was dedicated to the critical assessment of policing, tackling grievances from bigotry and coercion to violence and corruption. Roubille’s design—showing a plainclothes agent of the morality police being shot by a female offender on the street—visualizes the negative consequences of the duplicity of undercover police work.45 Removed from the scabbard of their official uniform, the agent des mœurs is transformed into a concealed, illegal weapon mobilized against unsuspecting citizens or worse, easily confused with a common criminal.46 The confusion between perpetrator and victim is embodied by the woman who, still holding the smoking gun, warns her fellow prostitutes, “Only dead, ladies, will he never be mistaken again.”47 The initiative of this capable woman, however violent, to resist arrest is echoed in Roubille’s authorship of the tag mort aux vaches on the wall behind the pair, at once a command and confirmation that death is the fitting punishment of police underhandedness.

Conclusion

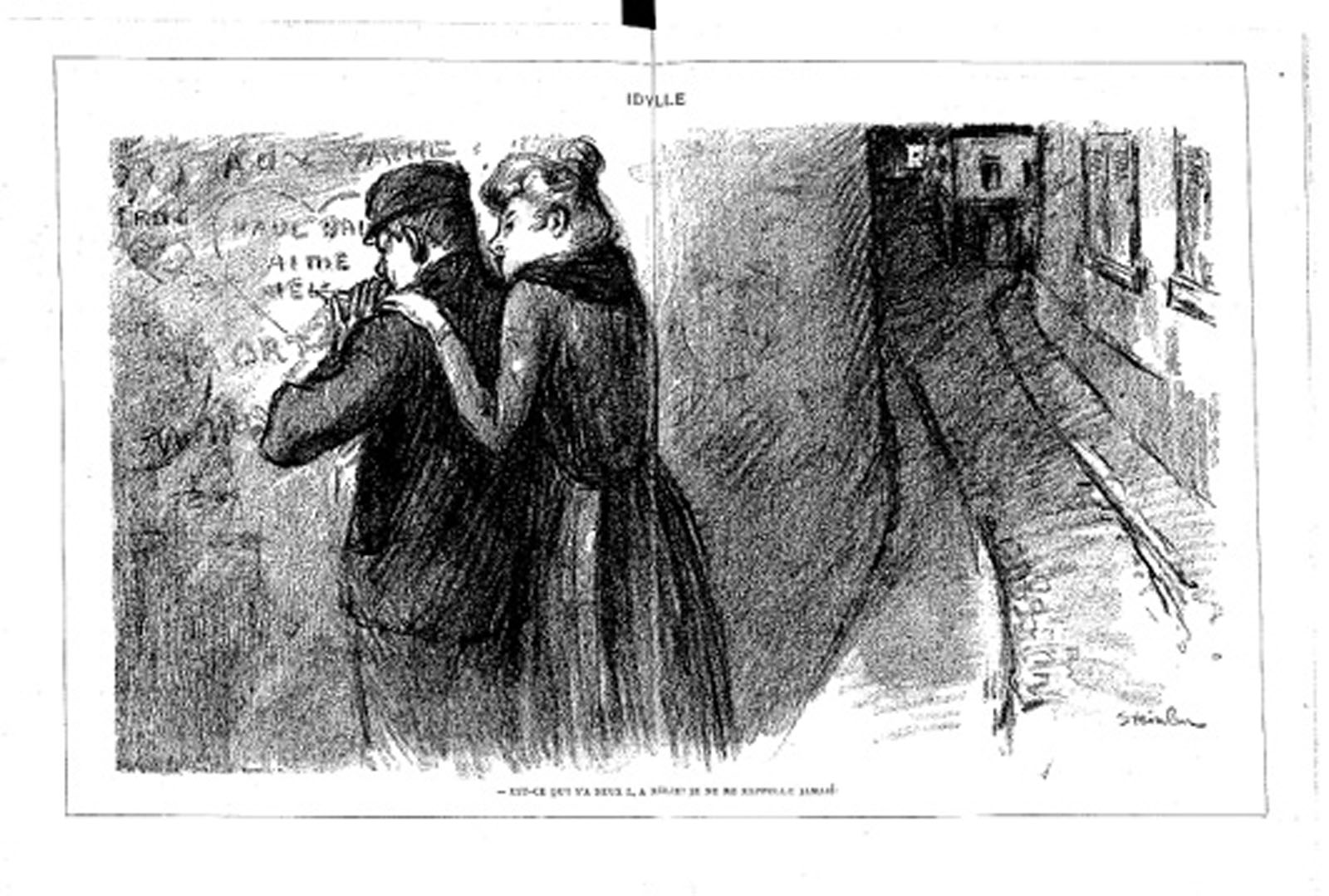

In January 1901, Steinlen published a two-page illustration in Le Frou-Frou that shows the same couple from Dans la rue at work on another inscription, this time a playful profession of their love (fig. 15).48 The heart containing their names overlaps messages previously scrawled on the wall, two of which bear snippets of the radical phrase mort aux vaches. As in L’Affaire Crainquebille, Steinlen’s composition of the image disrupts the inscription, forcing the viewer to reconstruct the insult for themselves. Interconnecting, fragmentary, and illegible, the urban writing on the wall suggests how the communicative potential of the city could be interrupted or redirected by citizens—and artists—in defiant acts of resistance open to all.49 In producing graffiti in print, Steinlen and Roubille also disrupted the ephemeral nature of the medium, transforming it into a durable and circulatory form: visibility on the countless kiosks in the street made their graphic graffiti at once multiple, mobile, and mutable, easily exchanged or replaced by another copy of the journal. Returning to the tag on rue Jean Poulmarch, we see that the practice of writing and re-writing in urban space continues to challenge the visual, social, and legal order imposed by authorities on the street; and mort aux vaches—an expression long associated with social, political, and legal delinquency—remains a potent means by which to oppose it.